If I have to be subjected to global discourse on this bullshit, then you can at least read what a trans person has to say about it.

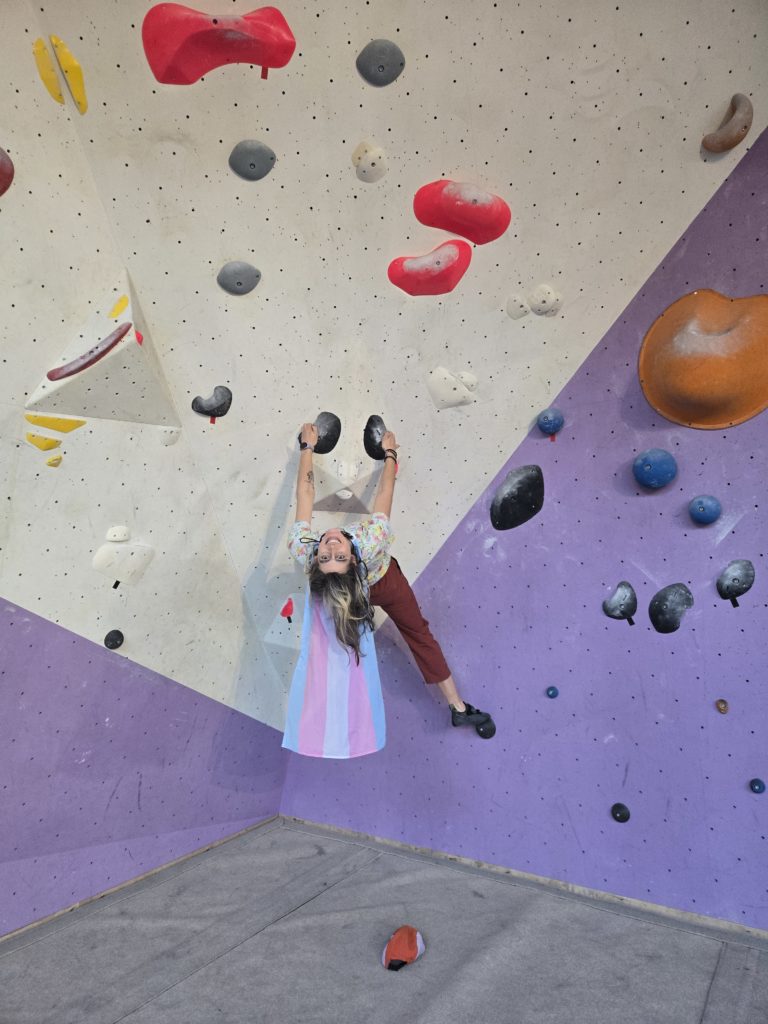

My Experience

As a trans person, and an American subjected to years of national (now international) media attention on this “issue”, I have thought about it a lot. I’m finally putting these thoughts to the page because I got interested in my first competitive sport after transitioning – archery. I took an intro lesson series at a club in Amsterdam, during which I asked my coach how official archery competitions would “handle my situation”, given that they have separate categories for men and women.

I am nonbinary, which to me is both an internal identity (I feel like neither a man nor a woman), and a physical descriptor of my body. I was born with typical male characteristics, underwent androgenic puberty, and later several years of hormone replacement therapy with estrogen, which my body now runs on full-time. A more specific word is transfeminine.

My body, like the millions of other trans or intersex bodies, does not fit cleanly in either category of “male” and “female”. Sports are not the only aspect of our society that is segregated by gender, but a good example of how these structures cause harm – and not just to the LGBT community. Anyone who doesn’t conform to typical gender norms is at risk of exclusion, harassment and discrimination by these systems, which fail to even fulfill their purpose of ‘fair competition’.

Playing with the Girls

I think sport – like making art, or communicating, or enjoying good food – is one of the most fundamental human activities and should be open to everyone. It benefits our health, social lives, entertainment, self-esteem, and more. In particular, the social environment of team sports is hugely beneficial for child and adolescent development, teamwork, leadership, and other vital skills for generally good human beings. I’m grateful to have gotten useful skills from my experiences with youth sports, but aside from that, they were generally hostile and deeply uncomfortable environments for me. At the time, I concluded I was just not into sports culture, and eventually stopped participating altogether.

Now, with the clarity of self-understanding and emotional awareness that comes with adulthood, I understand these experiences as threads in the tapestry of my trans journey. Of course I was uncomfortable and felt out of place – I was a girl* told to play with the boys. And if I had been able to know myself at that age, I would have wanted to play with the girls.

Like many trans people, I feel grief about the childhood I never got to live. I can’t describe what it would have meant to me to be seen, and accepted, in “girl” spaces as a kid. Without the ever-present friction between myself and my male peers, I could have lived more freely, enjoying the full love I had for sports, camping, art, and so much else. So when I hear adults today argue that ‘boys shouldn’t be allowed to play with the girls’, this grief all comes back up, as I think about the kids today who do get to know themselves as trans, but not live it.

Excluding Participation

The decision to transition was not one I made lightly. I knew it would make many aspects of my life more complicated and difficult. A world built by and for dominant social groups is not very accommodating to those on the outside.

Before even entering a competition, I have faced several barriers that most cisgender (non-trans) archers do not. First I took on risk visiting an unknown community group and social space, unsure if I would be respected or welcomed. When I knew I at least had a supportive coach and classmates, I still had to seek information myself about trans athletes in competitions. And now I’m writing this because I have to explain myself to get that answer.

I literally live on the margins of these pages, absent from competition categories and rules. I am trying something fun and rewarding, but facing unnecessary obstacles due to something outside my control. I want to participate in these competitions, but I also know that just getting there would be the least of my struggles.

Enforcing Gender Norms

Since starting my transition, I have shifted my reaction to being misgendered from something personal, to something fascinating. How someone else sees me has infinitely more to do with them than it does with me. Everyone has different conceptions of what a “woman” should be and look like; for some people, long hair is enough. For others, a deep voice convinces them I must be a man. Brow shape, height, clothes, makeup, even posture and mannerisms, all get filtered through someone’s “gender” pattern-recognition boxes in their brain.

What I’ve just described is a neutral state of the human experience – I think it’s fine we all have these subjective lenses. Although we should learn about them, lest we mistake subjectivity for objective truth, as this ‘debate’ has taken us toward. Because once we institutionalize these lenses beyond the individual, those systems reinforce these biases on a wider scale. Gender norms vary across different cultures, ethnic groups, and time periods, so institutions tend to reinforce norms of the groups that build them (typically: western, white, male viewpoints). Many other scholars have written much better than I could about the intersections of gender and racial oppression, but suffice to say: these systems of enforcement disproportionately impact people on the margins of society.

I use the word ‘enforcement’ because although many believe gender to be a ‘natural reality’, these systems require human-made oversight, policies, and processes to be implemented. And in their enforcement, they impact more than just trans people – in particular, other marginalized groups. When we adopt this gender-policing paranoia, we start to look for reasons someone might not belong: broad shoulders, large hands, short hair, a deep voice, facial hair – none of which are features exclusive to trans bodies. These things we see as signs of otherness are not objective, but informed by our own perspective and experiences.

Fair Competition and “Biological advantage”

In a rare moment of self-assuredness, I actually believed when my coach told me I could become great at archery. But any ambition I felt was quickly overtaken by anxiety. I‘ve seen the kind of harassment trans athletes face in high-level competitions. Even if I could reach that skill level someday, staying motivated in the face of such public vitriol would be difficult, if not impossible.

When discussing this issue with my mom earlier this year, she remainend convinced that trans women had some kind of universal advantage over their cis competitors, and that something had to be done about it. I asked her “so trans women can never be allowed to win?”, and was surprised at how quickly and matter-of-factly she said “yes”. This opinion is not unique to her, but demonstrates the true nature of these reactions to trans people in sports: it’s only about fair competition for cis people.

This is also reflected in the fact that most discussion on this issue revolves around trans women in women’s leagues, while trans men in men’s leagues are largely ignored as any sort of threat. If ‘biological males’ really do have a universal advantage in sport, then shouldn’t something be done to ensure trans men can enjoy fair competition as well? No, because these arguments about fair competition are disingenuous, or misguided at best. Instead of addressing ‘unfair biological advantages’, they seek to exclude trans people from sport entirely.

Take a look at the bodies of top-level athletes across different sports, and you will quickly notice patterns emerge. Height, weight, musculature, wingspan, and other features outside of an individual athlete’s control make them better-suited toward some sports than others. We already allow, and even celebrate, biological advantage in sports (consider reactions to how Michael Phelps’ unique body allows him to reach unprecedented records in swimming, compared to any trans woman even remotely competitive in her sport). Gender-segregation is a shorthand method of filtering large populations by physical characteristics, but inevitably fails at creating truly fair competition.

P.S. There is also a lot to say about society’s tolerance for unfair non-biological advantages in sport, such as money, national origin, education access, and more.

HOW to Be better

These structures are BUILT, meaning they can be changed, and we can create a new reality that is more inclusive. All it takes is people motivated to see something different, and those in charge willing to try new things.

Reduce Barriers to Entry

- If you must collect gender data on your athletes, provide at least 3 options (man, woman, other/nonbinary). Bonus points if you allow write-in options!

- Create and post a diversity or inclusion statement for your organization (and make sure your members actually follow it!)

- Train your coaches, volunteers, and competition officials on gender inclusive language and practices.

- Perform outreach to underrepresented gender(s) to increase club diversity and representation for future participants.

Desegregate Your Competitions

- Allow men and women (and everyone) to practice, train, and compete in the same settings

- Use specific, measurable criteria to create divisions necessary for fair competition

- Ex: height/weight, average scores, reaction time, agility, lung capacity, whatever!

- Promote & celebrate athletes equally across all divisions, regardless of gender

If you REALLY HAVE TO…

- You don’t. If there is a rule, or policy, advocate for its change; restructure your team/club/league however you can in the meantime.

- Create mixed, all-gender, and/or nonbinary categories alongside “men” and “women”

- Allow competitions to occur simultaneously / mixed across genders, and only separate out results by gender.

- Create an easily-accessible statement of how gender categories are determined (self-identified, government ID, hormone levels, etc), and specifically explain how trans, nonbinary, and intersex athletes may participate.

That’s It!

As usual, this took longer than I expected to write! But it was a good exercise, and hopefully the first of many posts here about my life perspective (which I generally think is good and thoughtful and worth sharing).

Until next time!

💜🏳️⚧️✌️Ada

P.S. Other Common Talking Points that Aren’t Worth Arguing Against but I Wanted to Briefly Address Anyway

“So a man can just call himself a woman to win in women’s competitions?”

No cis man or trans woman has ever taken HRT in order to excel in women’s sports. If you took time to look into the economic, psychological, and especially social costs of being trans and transitioning, you would understand no amount of recognition in athletic competition is worth that.

“It’s about protecting women”

Trans women are women, and worthy of the same protections. If you’re concerned about injuries in full-contact sports, maybe we just shouldn’t support them? A debilitating injury to an athlete isn’t somehow made ‘ok’ if it was caused by a cis person.

“It’s about women’s sports”

Women’s sports are generally less respected, spectated, and financially supported by our society. Women’s leagues are already functionally second-class to men’s, so if you care about women’s sports, how about focusing on this disparity? Keeping trans women out of these leagues does nothing but reinforce the idea that women’s sports are inferior versions of men’s

Leave a Reply to Sanne van Amerongen Cancel reply